G2333: Youth and Families, Healthy Living

Pearl Avari, Graduate Student

Amy R. Napoli, Early Childhood Extension Specialist and Assistant Professor

Holly Hatton-Bowers, Early Childhood Extension Specialist and Assistant Professor

University of Nebraska–Lincoln College of Education and Human Sciences

This guide provides information about workplace burnout on early childhood educators. In this guide, the term “educators” refers to all childcare providers working with children aged birth to 5 years. Research-based techniques and strategies are provided to support early childhood educators in effectively managing their work stress, and to increase psychological well-being and workplace engagement.

The first five years of a child’s life are a crucial period of development. It is during these years that children develop socio-emotional, cognitive, language, and regulatory skills. Early childhood educators play an essential role during this rapid stage of development for children. Over 75% of children in Nebraska under the age of six reside in homes where all adults have working status, making the role of early childhood educators even more important (Buffet Early Childhood Institute, 2020). Early childhood educators have many workplace demands, such as caregiving responsibilities, engaging in professional development and training, managing and engaging in successful parent-educator relationships, and staying up to date with emerging technological teaching tools. Meeting these constant demands can influence the physical, psychological, and organizational well-being of educators. Working in early childhood education also requires higher physical work demands (e.g., lifting children and moving furniture around for daily activities), and when psychological factors such as stress, anxiety, or depression occur, the combination can lead to lower job satisfaction and commitment.

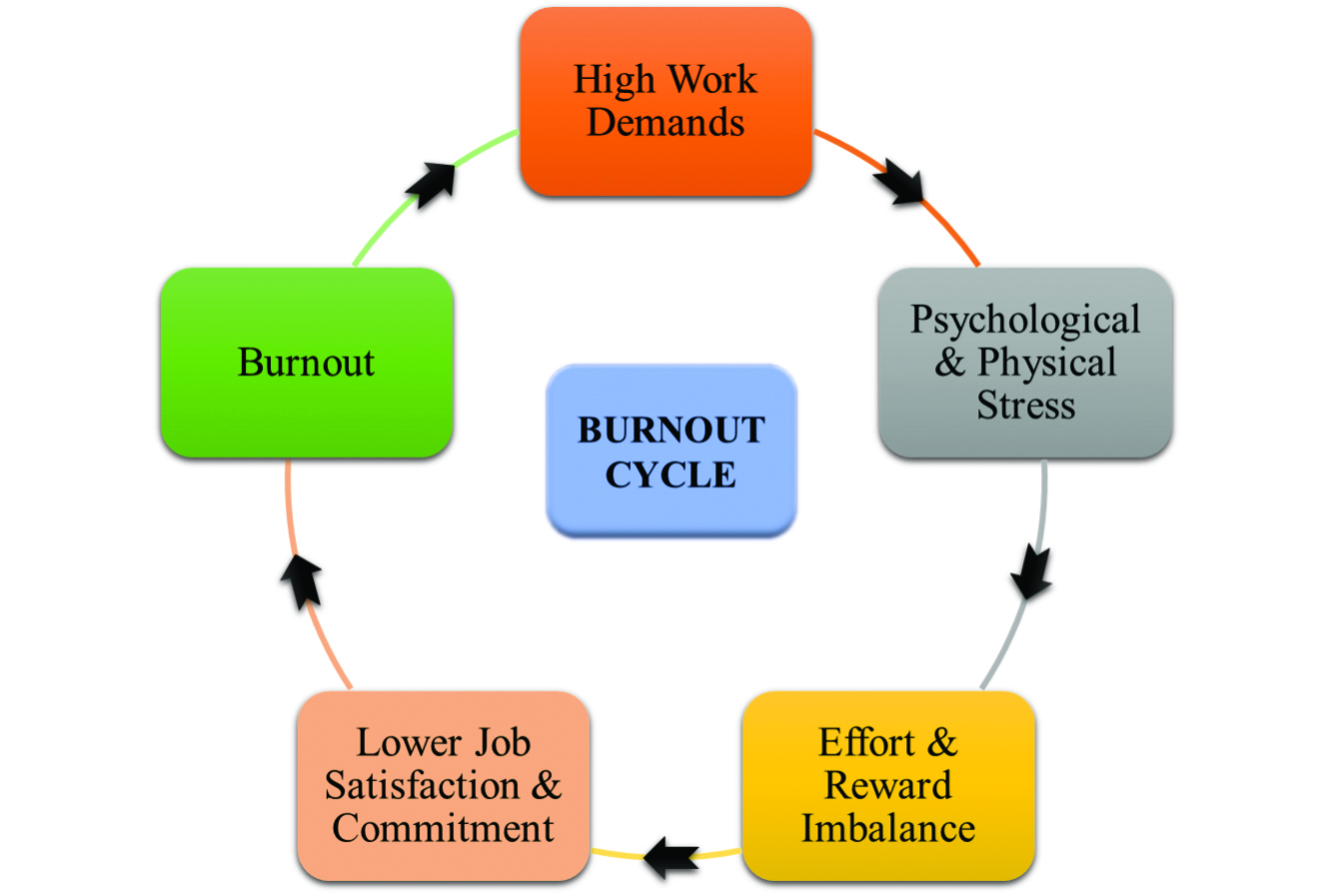

In Nebraska, early childhood educators surveyed from 2015–2016 reported clinically depressive symptoms ranging from 8% in home-based childcare to 10% in PreK programs, with the majority (86%) of early childhood educators in Nebraska reporting experiencing depressive symptoms (Nebraska Early Childhood Workforce Survey, 2017). When educators perceive the continual unequal balance between their efforts and the rewards they gain at their workplace, the “burnout cycle” begins (see Figure 1). Burnout can adversely affect the quality of care and education children receive, and results in occasional or chronic absenteeism on the part of the educator, employee turnover, and educators leaving the profession altogether. It is important to support the health and well-being of the Nebraska early childhood workforce to be able to provide high-quality care and education for children.

Workplace burnout has commonly been defined as long-term occupational stress and unpleasant and negative feelings that arise due to different workplace stressors. Early childhood educators may experience stressors that fall within three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased personal accomplishment.

Figure 1. Common Stressors Early Childhood Educators Face

Educators who experience high burnout levels can become less sensitive to children’s needs, less engaged in daily activities, and more distant, and they can miss opportunities to actively engage children in their learning process. This can negatively impact children’s social-emotional and academic outcomes. High educator burnout levels also result in high turnover rates, an issue that drastically affects the quality of childcare in Nebraska. More than three-quarters of childcare centers in Nebraska reported turnover of lead and assistant teachers (Buffet Early Childhood Institute, 2020).

Experiencing long-term stress at the workplace is a common predictor of early childhood educators’ feelings of burnout. The sources of stress experienced by early childhood educators are multi-faceted and are impacted by the systems they work in.

Spill-over of prolonged stress in the educators’ personal lives can hinder their work-life balance and make the burnout cycle seem endless.

Early childhood educators are crucial for young children’s quality learning and development. When educators are at their best, they help create a supportive socio-emotional environment for the classroom. To provide the best care to children, it is essential for educators to be supported. Supportive systems and policies are critical for addressing burnout. Prioritizing self-care and wellness is also essential.

Some strategies that should be considered within the policies and systems of the program, as well as healthy ways to manage stress, are listed below. For any strategy to be sustainable, there needs to be support, and wellness strategies should not be solely the responsibility of the educator.

Buffet Early Childhood Institute (2017) Nebraska Early Childhood Workforce Survey. https://buffettinstitute.nebraska.edu/our-work/elevating-the-early-childhood-workforce/survey

Buffet Early Childhood Institute (2020) Nebraska Early Childhood Workforce Commission. https://buffettinstitute.nebraska.edu/our-work/early-childhood-workforce-commission

Cumming, T., & Wong, S. (2019). Towards a holistic conceptualization of early childhood educators’ work-related well-being. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 20(3), 265–281.

Edwards, C. P., Hart, T., Rasmussen, K., Haw, Y. M., & Sheridan, S. M. (2009). Promoting parent partnership in Head Start: A qualitative case study of teacher documents from a school readiness intervention project. Early Childhood Services: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Effectiveness, 3(4), 301–322.

Hatton-Bowers, H., Smith, M. H., Huynh, T., Bash, K., Durden, T., Anthony, C., Foged, J., & Lodl, K. (2020). “I will be less judgmental, more kind, more aware, and resilient!”: Early childhood professionals’ learnings from an online mindfulness module. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(3), 379–391.

Hwang, Y.-S., Medvedev, O. N., Krägeloh, C., Hand, K., Noh, J.-E., & Singh, N. N. (2019). The role of dispositional mindfulness and self-compassion in educator stress. Mindfulness, 10(8), 1,692–1,702.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2015). Transforming the workforce for children birth through age 8: A unifying foundation. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 706 p.

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S.E., & Leiter, M.P. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory-Manual (3rd ed). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Nebraska Department of Education. (2020, March 14) Early Childhood Training Center. https://www.education.ne.gov/oec/early-childhood-training-center/

Phillips, D., Austin, L. J. E., & Whitebook, M. (2016). The early care and education workforce. The Future of Children, 26(2), 139–158.

Roberts, A. M., Iruka, I. U., & Sarver, S. L. (2017). Nebraska Early Childhood Workforce Survey: A focus on providers and teachers. Retrieved from Buffett Early Childhood Institute website: http://buffettinstitute.nebraska.edu/workforce-survey

Sarver, S.L., Huddleston-Casas, C., Charlet, C., & Wessels, R. (2020). Elevating Nebraska’s Early Childhood Workforce: Report and Recommendations of the Nebraska Early Childhood Workforce Commission. Omaha, NE: Buffett Early Childhood Institute at the University of Nebraska. © 2020 Buffett Early Childhood Institute.

Whitaker, R. C., Dearth-Wesley, T., & Gooze, R. A. (2015). Workplace stress and the quality of teacher–children relationships in Head Start. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 30 (part A), 57–69.

Whitebook, M., McLean, C., Austin, L. J. E., & Edwards, B. (2018). The early childhood workforce index 2018. University of California, Berkeley: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/early-childhood-workforce-2018-index/.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Nebraska Extension publications are available online at http://extension.unl.edu/publications.

Extension is a Division of the Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln cooperating with the Counties and the United States Department of Agriculture.

Nebraska Extension educational programs abide with the nondiscrimination policies of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and the United States Department of Agriculture.

© 2021, The Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska on behalf of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension. All rights reserved.