Holly N. Hatton-Bowers, Assistant Professor, Extension Early Childhood Specialist

Kara L. Cruickshank, Graduate Student, Child, Youth and Family Studies

Donnia E. Behrends, Extension Educator

Emily A. Hulse, Community Program Coordinator, Children’s Center for the Child and Community

The decision to breastfeed is influenced by many factors, from personal motivations to societal circumstances. Whether you are a woman considering breastfeeding, a friend, family member, or professional supporting a breastfeeding woman, this guide will provide research-based information to help inform and support that decision with cultural awareness and sensitivity. Information about the benefits of breastfeeding, common barriers to the practice, cultural considerations, and resources for support are presented.

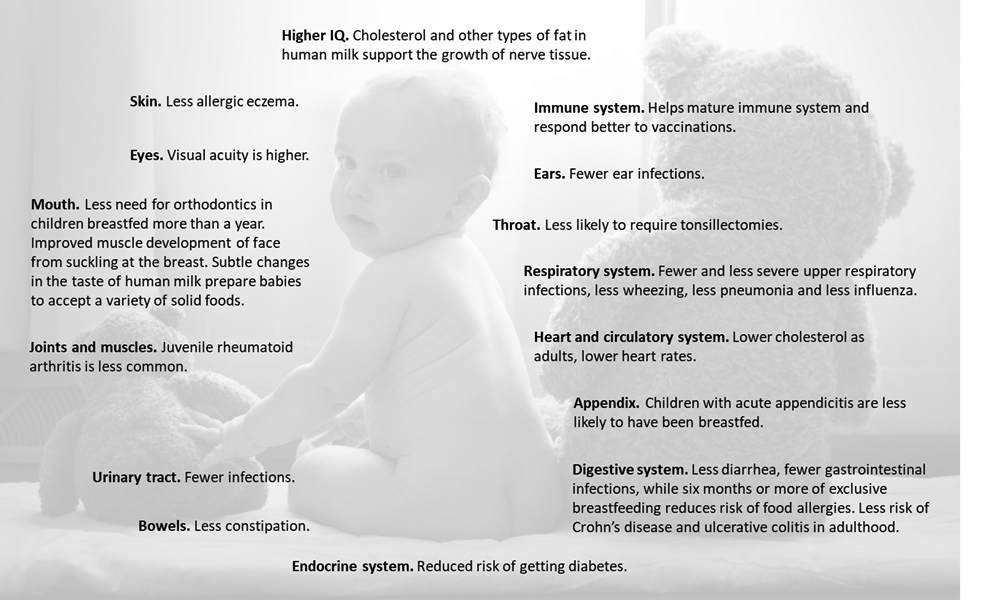

Breastfeeding is an important practice for both infant and mother. Breastmilk provides the nutrition and nourishment a typically developing infant needs for the first six months of life. It is known to uniquely support each infant’s immune system while they develop, which helps to protect against respiratory and gastrointestinal infections. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of an infant’s life, followed by the introduction of appropriate solid foods with continued breastfeeding until at least 12 months of age. These nutritional benefits of breastfeeding continue into the second year of life. In fact, the nutritional components (proteins, vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates, and fat) in the mother’s breastmilk change over time to meet the nutritional needs of the child. Additionally, breastfeeding may reduce the chance that a child becomes overweight or develops certain diseases in the future. Breastfeeding is also associated with a lower risk of sudden infant death syndrome.

Women can also experience benefits from breastfeeding. Women who exclusively breastfeed typically lose more weight after giving birth than women who feed their babies formula. Breastfeeding reduces the risk of breast and ovarian cancer, protects against osteoporosis and diabetes, reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases and postpartum depression, and can improve birth spacing. Breastfeeding saves an average of $1,500 per year, and women who breastfeed are less likely to miss work to take care of sick children. Finally, breastfeeding can benefit both mother and infant by helping to create a close emotional bond.

Figure 1. Benefits of breastfeeding.

Collectively, these established benefits of breastfeeding resulted in Healthy People 2020 developing national objectives to increase the proportion of women who breastfeed their babies.

These objectives are developed and published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

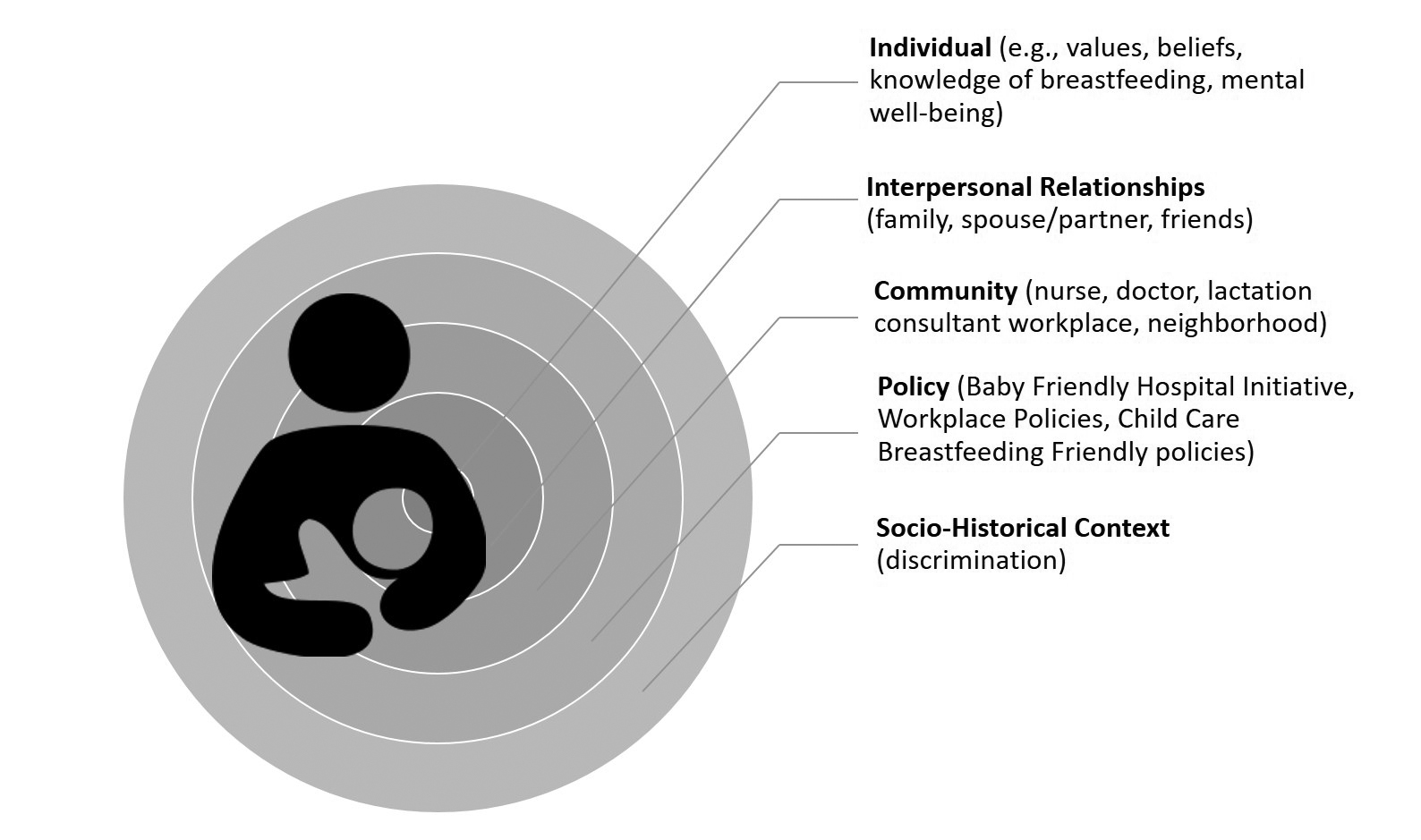

Figure 2. Social-ecological model of breastfeeding influences.

Despite the benefits of breastfeeding, the 2016 Breastfeeding Report Card from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that 80 percent of mothers initiate breastfeeding, but by three months, only 42 percent continue to exclusively breastfeed. While breastfeeding trends have improved in the past decade, many women continue to experience barriers and challenges. Some of these common challenges are pain, too little or too much milk, lack of information or experience, depression or anxiety, difficulty pumping at work, and lack of social support.

The most common barrier to breastfeeding among all women is employment; exclusive breastfeeding is most likely to end when women return to work. Unfortunately, some women are more negatively affected by these factors than others. For instance, women of all races who are considered low-income are the least likely to breastfeed. Research finds that African American women in particular breastfeed at the lowest rates. Returning to work is a common barrier as they tend to return to work sooner and are more likely to face unsupportive work environments, such as shorter maternity leaves and less flexible work schedules. Research also finds that breastfeeding rates among some immigrant women decline when compared to breastfeeding rates in their countries of origin.

One way to look at the factors that support or hinder breastfeeding is through a social-ecological framework. Figure 2 provides a framework of the possible influences impacting a woman’s decision to initiate and continue breastfeeding. Imagine the breastfeeding woman at the center of the circle. Each ring represents influences at a different level. The influences closest to her are represented in the inside rings. As you move outward, the influences become less direct, but they still affect the woman. This framework can be applied to breastfeeding women in any circumstance by substituting the unique influences in their lives at each level. Try it out!

If you are a professional supporting a breastfeeding woman, this framework can help you identify where additional resources are needed. If you are a breastfeeding woman, this may help you identify your motivations, barriers, and supports when making the decision to breastfeed and what influences your decision to continue breastfeeding.

Women lacking breastfeeding support are more likely to stop breastfeeding sooner. Support for breastfeeding is important and can come from many different sources, including health professionals, mothers, grandmothers, trusted friends, child care providers, and community members. Community organizations dedicated to supporting breastfeeding practices are also an important resource. For example, peer counseling and lactation consultants are found to be the most successful resource for supporting various women in breastfeeding promotion and support. Finally, the culture and society surrounding the breastfeeding mother may affect her decision to begin and continue breastfeeding.

Table 1. Unique Cultural Influences

|

While this list is not exhaustive, it provides some examples of interpersonal, cultural, or ethnic beliefs, attitudes, or practices that may play a role in a woman’s breastfeeding decision. |

|

|

African American |

Some cultural beliefs that have been identified in the literature include the belief that “milk runs right through” the infant and that breastmilk or formula cannot satisfy the baby. This belief is tied to the early introduction of solids and putting cereal in the infant’s bottle. Another cultural belief identified in some communities is a purely sexualized view of breasts. This view discourages women from breastfeeding because it is considered inappropriate for breasts to be viewed in public or used for feeding. |

|

Asian Indian (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka) |

Breastfeeding is highly valued and strongly encouraged. Traditional feeding cups called paladai may be used when women have difficulty breastfeeding. Following birth, recuperation time is believed to be 40 days long, during which the mother is encouraged to stay at home, rest, and eat special foods. |

|

Hispanic/Latin American |

Variations in breastfeeding practice are usually influenced most by country of origin and level of acculturation (i.e., acceptance and practice of dominant culture). Initiation for breastfeeding rates are higher in Chile, Ecuador, and Columbia (95 percent or higher), and lower in Bolivia (59 percent), Mexico (38 percent), and the Dominican Republic (10 percent). Puerto Rican women have significantly lower rates of breastfeeding than Mexican American women. Practice may vary based on geographic location in the United States, too. Hispanic women living in Western states are less likely to breastfeed than Hispanic women living in Eastern states. Societal support and traditional beliefs affect the decision to begin and continue breastfeeding. For example, in Mexico, breastfeeding is the norm in families and society. This is supported by the social reality that fewer women work outside the home. When they move to the United States, more women work outside the home. Some may think formula is better because of the perception that breastfeeding is not valued in the U.S. Sometimes, Latina women decide to use formula because they believe that fatter babies are healthier, and formula is typically related to babies being heavier. Another traditional belief that may impact the choice to breastfeed is that a mother’s negative feelings, such as anger, depression, or fright, may harm or taint the milk. When a mother experiences these feelings she is discouraged from breastfeeding. |

|

Asian |

Traditionally, for some Chinese and Vietnamese women, pregnancy is viewed as a “hot state”. In childbirth, women are seen as losing this heat through the loss of blood, and women go into a “cold” state. After childbirth, they may follow a specific diet based on the traditional practice of restoring “heat” to their body by eating foods that are warm or hot in temperature which is believed to protect the flow of breast milk and the baby. Practices also include avoiding spicy foods, and preferring plain foods or eating fish soup and papaya soup. Some Korean women believe that breastfeeding should start on the third day postpartum and that seaweed soup increases milk production. |

|

Somalian Immigrant |

Somalian immigrants who are Muslim may be strongly influenced by their religion. Breastfeeding is recommended in the Koran for two years, and women are permitted to put off fasting until they are no longer breastfeeding. Another cultural perspective is that “plump” children are stronger and healthier. |

Table 1 highlights some unique cultural beliefs and practices. It is important to recognize these beliefs offer information that may not characterize everyone’s experience. As an example, a person who is Latina will have both shared and differing experiences within and beyond her ethnicity.

The following strategies to promote and enhance breastfeeding can be helpful for women wanting to breastfeed.

Promoting and enhancing breastfeeding is a multifaceted issue, encompassing interventions at multiple levels, from individual support and education to system-level advocacy and policy change. The following lists include tips and suggestions for promoting and enhancing breastfeeding across multiple system levels. One very important strategy is to use culturally competent skills. Understanding how someone’s culture affects that person’s decisions about breastfeeding can help you provide support in a culturally sensitive way. This requires both an understanding and appreciation of one’s own culture and that of another. Cultural competence is a phrase that has been used to describe this ability. The skills of cultural competence take continual practice, but they will enhance your ability to work with others who come from different backgrounds.

While it will take an integrative approach across all systems to address the barriers that impact women’s decisions to breastfeed and continue breastfeeding, recognizing the role of cultural competence is an important initial and ongoing step.

In asking questions and learning of the mother’s beliefs you can develop a respectful plan of action to support breastfeeding that incorporates selected aspects of the mother’s culture.

Lincoln: 5930 S. 58th St., Lincoln, NE 68516; (402) 423–6402

Omaha: 10818 Elm St., Omaha, NE 68144; (402) 502–0617

The Ecological Model of Breastfeeding Women is adapted from the ecological model of Johnson, Kirk, Rosenblum, & Muzik, 2015.

Johnson, A., Kirk, R., Rosenblum, K.L., Muzik, M. (2015). Enhancing breastfeeding rates among African American women: a systematic review of current psychosocial interventions. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10, 1, 45–62. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2014.0023

Berlin, E. A., & Fowkes, W. C. (1983). A Teaching Framework for Cross-cultural Health Care—Application in Family Practice. Western Journal of Medicine, 139(6), 934–938.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Nebraska Extension publications are available online at http://extension.unl.edu/publications.

Extension is a Division of the Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln cooperating with the Counties and the United States Department of Agriculture.

University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension educational programs abide with the nondiscrimination policies of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and the United States Department of Agriculture.

© 2017, The Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska on behalf of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension. All rights reserved.