G2224

Sugar Beet Seedling Rust

Sugar beet rust has a unique life cycle that is essentially harmless for producers, but has caused serious, sporadic losses to Colorado spinach growers. This publication will help recognize sugar beet rust symptoms and characteristics to avoid needless treatment.

Robert M. Harveson, Extension Plant Pathologist

- Introduction

- First Report From Colorado

- Pathogen Life and Disease Cycle

- New Report From Nebraska

- Survey of Sugar Beet Fields 2009-2010

- Conclusions

Introduction

Sugar beet seedling rust, caused by the fungal pathogen Puccinia subnitens, is a disease of Chenopodiaceous crops that has rarely been observed in commercial sugar beet production. Due the pathogen’s unique life cycle (see below) it is essentially harmless for sugar beet producers, but has caused serious but sporadic losses to Colorado spinach growers. The purpose of this publication is to alert and educate producers and consultants on recognizing the symptoms and characteristics of this disease in order to avoid wasting resources by needlessly treating it in the event it appears again in this area.

First Report From Colorado

The first published report of this disease on sugar beets was from Colorado in 1914. The rust was found occurring frequently during the 1912-1913 seasons from multiple fields in the Arkansas Valley near Rocky Ford, Colo., but the conclusion was that the disease did not severely affect the crop during these two seasons.

Pathogen Life and Disease Cycle

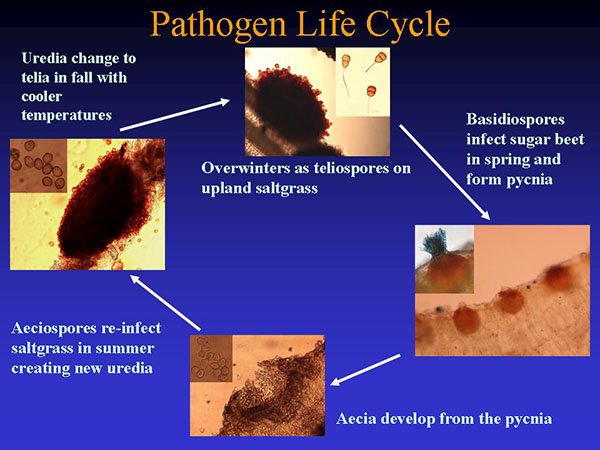

The pathogen has a very complex life cycle consisting of five distinct spore stages, the basidial, pycnial, aecial, uredial, and telial stages. The entire cycle is completed on two different hosts (Figure 1), in contrast to the rust diseases of dry beans or sunflowers that produce the same spore stages but infect only those two crops. Only two of the spore stages (pycnial and aecial) occur on the hosts of economic importance, sugar beet and spinach, while the remaining stages infect several species of saltgrass, primarily the inland saltgrass (Distichlis spicata). These species are warm season grasses native to arid areas of the western United States. They are very drought tolerant plants, flourishing in the strongly alkaline soils found throughout western North American and the Great Plains.

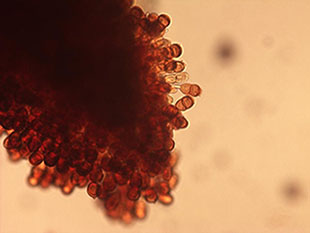

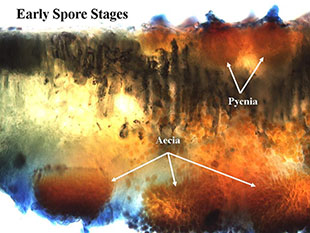

In early spring, the teliospores germinate after overwintering on inland saltgrass to produce basidiospores, which then are blown by wind where they can infect sugar beets or other alternate hosts, including spinach, and numerous weed species such as lambsquarters (Figure 2). Infections by the basidiospores give rise sequentially to the pycnial and aecial spore stages. Pycnial lesions are circular and light yellow, measuring 2-5 mm in diameter (Figure 3A). Flask-shaped pycnia are generally found on the upper leaf surface and after fertilization occurs, the aecia are formed on the lower leaf surface directly below the pycnia (Figure 4). The aecia consist of clusters of yellowish-orange, rounded structures (Figures 3B) containing aeciospores. Later the newly formed aeciospores then re-infect the inland saltgrass, creating new uredia and telia, completing the life cycle (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Life cycle of the sugar beet seedling rust pathogen, Puccinia subnitens. |

|

|

|

Figure 2. Young aecia arranged in circular patterns on the underside of a common lambsquarters leaf. |

Figure 3. Circular, light-yellow pycnial lesions on the upper surface of a sugar beet cotyledon (A); yellowish-orange aecial pustules arranged in rings on the lower cotyledon surface (B). |

|

|

|

|

Figure 4. Thin section of infected sugar beet leaf showing flask-shaped pycnia on the upper leaf surface, and aecial cups and developing aeciospores on the bottom leaf surface. |

Figure 5. Field-infected, young sugar beet plants exhibiting pycnial lesions on cotyledons. |

New Report From Nebraska

In mid-May 2009, young sugar beet plants were first observed exhibiting signs (pathogen structures) indicative of sugar beet seedling rust in a field near Bayard, Neb. (Figure 5). This was after an extended period of unusually cool and wet weather throughout the western Nebraska Panhandle in April and early May. Disease incidence (percentage of infected plants) in this beet field approached 25 percent although lesions were restricted primarily to the cotyledons, and it was further noted that this particular sugar beet field was surrounded by stands of inland saltgrass also infected with the telial stage of a rust pathogen (Figure 6), morphologically consistent with P. subnitens (Figure 7).

|

|

|||

Figure 6. Inland saltgrass infected with the telial stage of P. subnitens. |

Survey of Sugar Beet Fields 2009-2010

Based on this initial pathogen identification in Morrill County, Nebraska in mid-May, 2009, a survey of sugar beet production fields in western Nebraska was conducted between late-May and mid-June during the 2009 and 2010 growing seasons. This was to further document the incidence and prevalence of fields infested with this rare pathogen.

Over this two year period, 88 locations from eight western Nebraska counties (Scotts Bluff, Morrill, Box Butte, Banner, Kimball, Sioux, Cheyenne, and Sheridan) were scouted and 47 were identified with plants infected with pycnia and/or aecia of P. subnitens. Although the pathogen was readily found throughout the area in both years, the incidence within and among sites was lower in 2010 with only 30 percent of the monitored locations yielding infected plants compared to 65 percent in 2009.

Conclusions

The initial report of this disease indicated that infection appeared to be limited primarily to cotyledons (Figure 8) with symptoms being found occasionally on the first true leaves (Figure 9), resulting in the common name of “seedling rust” disease. The two-year survey conducted in Nebraska during the 2009-2010 growing seasons additionally documented the occurrence of multiple infections from many of the surveyed sites, with 20 percent of fields (18 of 88) from both years yielding plants exhibiting pycnial lesions on newly emerged leaves in mid- to late-June. These findings indicate the release of multiple flushes of basidiospores of the pathogen after May from the primary saltgrass host, followed by new infections on sugar beets long past the cotyledon or first true leaf stage (up to 5-6 the true leaf stage) (Figure 10).

|

|

|||

Figure 8. Field-infected, young sugar beet plant exhibiting both pycnial and aecial lesions, but restricted to the cotyledons. |

Figure 9. Pycnial lesion on one of the first true leaves of an infected sugar beet plant. |

|||

|

||||

Not only is this disease rare in appearance (the reports from Nebraska in 2010-2011 were the first published accounts of the natural occurrence of this disease on sugar beets in the field since 1914); it also is an atypical rust disease in several respects. Seedling rust on sugar beets is not economically damaging, due to the unique life cycle of the pathogen and the host growth stage at time of infection. Infection of the sugar beet occurs very early in the plant’s life. Repeated infections from the early spore stages (pycnial and aecial) and extensive damage to newly developing sugar beet leaves is not possible because the aeciospores that form in response to pycnial infection on sugar beets will not infect that same crop again that season. They will only re-infect the alternate saltgrass host.

Furthermore, this study has also provided a foundation for recognizing future outbreaks. By correctly diagnosing the disease rapidly and reporting the results, fungicide applications were avoided, which would otherwise have been made due to the unknown nature of the problem at that time.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension Publications website for more publications.

Index: Plant Diseases

Sugar Beet

Issued December 2013