G2198

Brain Development and Learning in the Primary Years

In the primary years, children are beginning to think in complex ways about themselves, their environment, and others. Teachers can play a role in honing children’s brain development and learning.

Jennifer K. Gerdes, Extension Assistant Professor

Tonia R. Durden, Early Childhood Extension Specialist

Lisa M. Poppe, Extension Educator

Developmental Directions

Children of preschool age are well-known for their focus on self, concrete ideas, exploratory interactions, and less complex thinking. In contrast, older elementary children (around age 8) are able to perform at the highest level of these directions. They can:

- think abstractly and symbolically,

- carry out steps to reach a goal,

- understand parts of a concept before they know the whole picture,

- understand the feelings of others, and

- think more complexly than preschool children.

Young children can think somewhat abstractly and even in complex ways but still need concrete experiences. They can follow directions but also enjoy exploring their own ideas. The concept of developmental direction illustrates the unique developmental level of kindergarten children. The developmental directions (see Table I) point to development as occurring from self to others, known to unknown, whole to part, concrete to abstract, enactive to symbolic, exploratory to goal directed, less accurate to more accurate, and simple to complex.

Table I. Examples of each developmental direction. |

|

Developmental Directions |

Example |

Known to Unknown |

When trying to teach a concept, the teacher connects the concept to something familiar to the child and then builds a bridge from what the child knows to what the child does not know. |

Self to Others |

Children must understand how the concept relates to them before they can generalize their knowledge to understanding others. This is especially relevant in social situations. |

Whole to Part |

Children must understand the big picture before they can understand the small parts that make up the big picture. When teachers understand the whole-to-part needs of children, they provide repetition of activities, time for exploring concepts and ideas, and teach specific pieces rather than general ideas. |

Concrete to Abstract |

For young children, learning stems from concrete experiences in which they can touch, taste, see, smell, and hear. Teachers utilize a variety of approaches to teaching a concept that includes both concrete experiences and more abstract teaching strategies, such as bringing in real leaves before showing pictures of leaves. |

Enactive to Symbolic |

Enactive representation occurs when children act out situations in their lives (role play, quacking like a duck after they see a duck). Symbolic representation, on the other hand, refers to using words or symbols (writing) to interpret experiences. Children need time to explore concepts through all modes of representation instead of relying on symbolic representation alone. |

Exploratory to Goal Directed |

Children need time to explore materials (spaces, concepts) before they are given specific directions about how to use the material in the appropriate way. Children need time to explore paint before being able to focus on completing the task desired by the teacher that uses the paint. In the same way, children need time to explore the new books about leaves before they are expected to look closely at the books. |

Less Accurate to More Accurate |

Children utilize trial and error to learn about the world. Over time and with experience, children learn the accurate information. The role of the teacher is to provide experiences and supports that help children revisit their misconceptions about concepts and build more accurate knowledge. |

Simple to Complex |

Tasks are presented to children in the simplest manner possible. This makes the task easier for children to navigate and helps them understand the task. Tasks are simplified when they are:

|

The Role of Brain Structure

Early childhood, the period from birth through age 8, is a stage of development unlike any other in the lifespan. Five- and six-year-olds make huge intellectual leaps during this time. Learning occurs differently during this period than in later years. One part of this difference is accounted for by the rapid changing of the brain and the influx of experiences that are new for children during this time. In 2000, a groundbreaking collection of research on early childhood brain development was released and changed what was known about how children learn and develop, and what kind of experiences they need to have during their early years to be successful.

This research tells us several things:

-

New knowledge (learning) must build from a child’s prior knowledge.

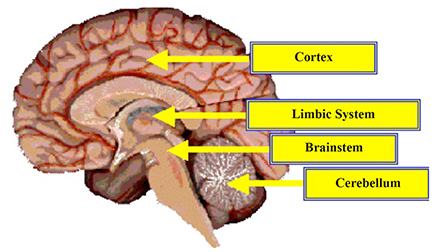

Figure 1. The parts of the brain associated with children’s learning.

- Experiences must be connected to each other for the child to make sense of the experiences. Learning occurs in the context of other experiences in the child’s life.

- The limbic system is the most ancient and primal part of the brain. It is the area of the brain that controls children’s motivations, emotions, affect, and feelings. Understanding the motivations and emotional states of children is essential for teaching them effectively.

- The cortex is where all of our thinking and processing of information occurs. This is where we learn academic concepts, logic, and self-regulation. This is the last part of the brain to fully develop.

- Understanding and valuing children’s emotional states and acknowledging their emotional needs is essential for teaching children effectively.

- The cerebellum regulates movement, balance, and coordination, and is highly functional in young children (Figure 1). This means that children need movement associated with experience to drive learning.

Putting It All Together

Learning must be tied to what children already know and incorporate concrete experience, representation, idea development, and the testing of ideas for deep understanding to occur. Children are developing rapidly during the primary years and are beginning to think in complex ways about self, their environment, and others. Teachers can play a role in honing these emerging skills by considering how to apply the developmental directions and concepts intentionally every day. Without a doubt, these early years shape a child’s overall outlook and engagement in lifelong learning.

Resources

A Kindergarten for the 21st Century: Nebraska’s Kindergarten Position Statement: http://www.education.ne.gov/oec/pubs/KStatement.pdf

Texts4Teachers: http://extensiontexts.unl.edu

The Learning Child: www.extension.unl.edu/child

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University: http://developingchild.harvard.edu/

References

Bruner, J. (1960). The Process of Education. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Dewey, J. (1938/1997). Experience and Education. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: experience as the source of learning and development. New Jersey:Prentice-Hall.

Kostelnik, M. J., Soderman, A. K., Whiren, A. (2011). Developmentally Appropriate Curriculum. (5th ed.) Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (2000). From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Zull, J. E. (2002). The Art of Changing the Brain: Enriching the Practice of Teaching by Exploring the Biology of Learning. Stylus Publishing: Sterling, VA.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension Publications website for more publications.

Index: Families

Preschool

Issued June 2013