G1963

Verticillium Wilt of Sunflowers in Nebraska

Verticillium wilt disease occurs in most sunflower-producing areas of the world, and is reported from Colorado, Kansas, and Nebraska. The disease’s symptoms, signs, identification, disease cycle, and management are covered in this NebGuide.

Robert M. Harveson, Extension Plant Pathologist

- Introduction

- New Report for Nebraska

- Symptoms and Signs

- Pathogen Identification and Disease Cycle

- Management

- Conclusions and Future Impacts

Introduction

Verticillium wilt, also known as leaf mottle, is caused by the fungus Verticillium dahliae. It was first described as a new disease of sunflowers in North America in the late 1940s, and initially attributed to V. albo-atrum. After 1970, the pathogen was recognized as V. dahliae, based on presence of true microsclerotia, and its ability to grow at temperatures exceeding 90°F.

Verticillium wilt is an important disease, known to occur in most sunflower-producing areas of the world. Its incidence and severity increased in the 1960s and 1970s, as sunflower acreage in North Dakota and Canada also increased.

The National Sunflower Association (NSA) still considers it a high priority issue, as economically significant losses are consistently reported, especially with confection hybrids, which generally lack genetic resistance.

In 2008, the NSA surveyor teams found Verticillium wilt in a quarter of the 156 fields inspected, with 32 percent of the plants in those affected fields having symptoms. South Dakota and Manitoba fields had the most severe disease levels.

New Report for Nebraska

In the Central High Plains, Colorado and Kansas have reported the pathogen only occasionally, and it is not considered a major disease problem. However, Verticillium wilt was found in approximately one dozen production fields, consisting of both confection and oilseed crops, in western Nebraska during 2008. These observations represent Nebraska’s first report for its presence. The disease was a limiting factor in several of these fields, but its long-term impact in Nebraska is unknown at this point.

Symptoms and Signs

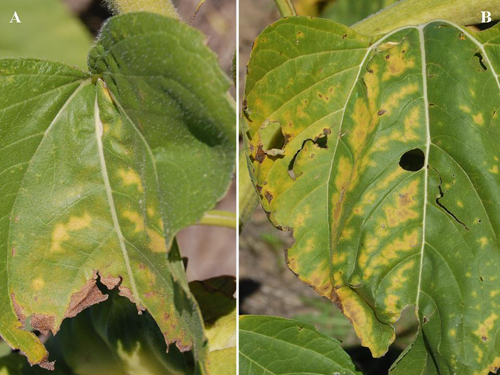

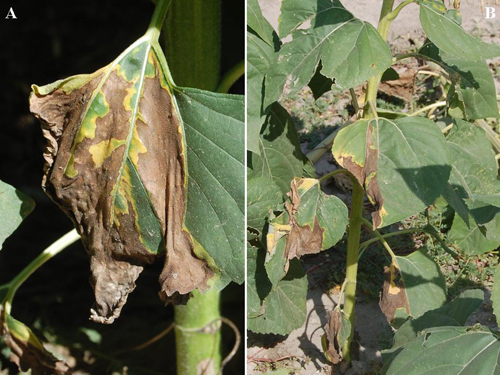

Disease symptoms first become evident at or near flowering. Small yellow areas between veins are the first visible symptoms to appear (Figure 1a). They merge and increase in size with time (Figure 1b), and eventually become necrotic. Symptoms develop on lower leaves first (Figure 2) as interveinal yellowing of tissues that develop progressively as the pathogen moves up the stems to newer leaves (Figure 3). The yellow areas become brown and necrotic, often with bright yellow zones surrounding necrotic tissues (Figure 4), giving the leaves a mottled appearance. This contrast between yellow and persisting green areas of the leaves was the origin for the disease name “leaf mottle.” Affected lower leaves will eventually dry and die (Figure 5a). This stage can be seen simultaneously with that of leaves affected to a lesser extent toward the top of severely infected plants (Figure 5b).

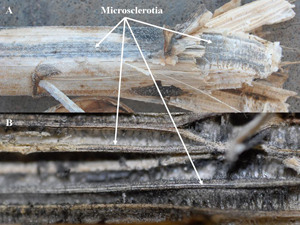

Infected stems in longitudinal section show reddish-brown, vascular discoloration (Figure 6). In severely diseased plants, black streaky patches may be seen late in the season on lower stems, consisting of thousands of tiny microsclerotia (Figure 7). Due to the systemic nature of the disease, the pathogen may be distributed throughout the plant and may be found in roots, stems, petioles (Figure 8), leaf midribs, or heads.

|

| Figure 1. (a) Early symptoms consisting of small yellow areas and (b) advanced yellowing symptoms prior to development of necrosis in yellow areas. |

|

|

|

| Figure 2. Interveinal yellowing and necrosis symptoms initiating on lower leaves. | Figure 3. Mottling symptoms progressing systemically up from bottom to new leaves on stalk. |

|

| Figure 4. Leaf mottle symptoms consisting of necrotic lesions surrounded by bright yellow zones. |

|

| Figure 5. (a) Lower leaf on infected plant exhibiting severe symptoms and (b) progression of leaf symptoms showing more severe symptoms at the bottom of plant. Note lowest leaf on bottom that is completely dead. |

|

|

|

| Figure 6. Reddish-brown vascular discoloration of infected plant (top) compared to a healthy stem (bottom). | Figure 7. Infected stalk late in the season with black streaks in vascular system (a) and internal pith (b), both consisting of thousands of microsclerotia. (Figure 7b - courtesy of Sam Markell, North Dakota State University). |

|

|

|

| Figure 8. Black necrotic tissues of petioles attached to a symptomatic leaf from an infected plant (on left in both pictures). The pathogen was isolated from petioles. | Figure 9. Advanced infection of a severely infected plant colonized by multiple root rotting organisms in lower stem and root (including V. dahliae). |

|

|

|

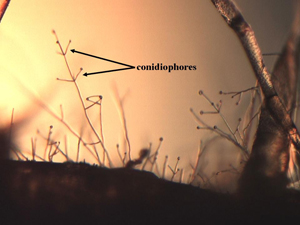

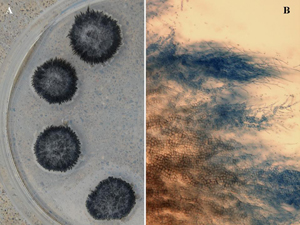

| Figure 10. Characteristic morphological features of V. dahliae with “verticillate” (arranged on central axis like spokes on a wheel) arrangement of conidiophores (spore-bearing structures) in multiple whorls. | Figure 11. (a) Characteristic colony growth in culture of V. dahliae, consisting of masses of black microsclerotia and (b) Mycelial growth of V. dahliae showing conversion of hyphal cells into irregular-shaped microsclerotia. |

Pathogen Identification and Disease Cycle

Infected sunflower root systems are often colonized by aggressive secondary organisms (Figure 9) making it harder to identify the slower-growing V. dahliae. However, using selective media or humidity chambers will help identify the pathogen, typified by conidiophores (spore-bearing structures) arranged in whorls around a central axis (Figure 10). This type of arrangement is referred to as “verticillate,” which is the origin for the pathogen name. In pure culture, the fungal growth is black (Figure 11a) due to masses of microsclerotia formed from chains of hyphal cells (Figure 11b).

V. dahliae is soilborne, survives in soil or plant residue as microsclerotia, and may remain viable in soils for several years without a host. The pathogen has a large host range consisting of more than 350 plant species, none of which are grass hosts (all tap-rooted plants).

Microsclerotia generally stay dormant until stimulated to germinate by host root exudates. Germinating microsclerotia produce hyphae (fungal vegetative growth) that infect roots and then progress into the plant’s water-conducting system, where the pathogen becomes systemic. As the disease progresses, the fungus can contaminate seeds with hyphae and microsclerotia, thus serving as a primary source of infection later. Movement of microsclerotia is likely the mechanism for the pathogen’s spread from its origin in the Americas throughout the rest of the world.

Management

- 3- to 4-year rotations with small grains or other non-host crops

- Proper seed sanitation

- Use of cultivars with genetic resistance where available

- Avoiding fields with a history of the disease

Conclusions and Future Impacts

Nebraska’s sunflower production acres have fluctuated greatly over the years, but solid trends toward increased interest in sunflowers seem to be in the near future.

Sunflowers fit well in many production systems as an alternative crop in dryland wheat/fallow rotations. They are also increasingly being used to lengthen the traditional irrigated rotations of dry beans, corn, and sugar beets.

Seed companies have traditionally used a specific resistance gene (referred to as the V-1 gene) to control Verticillium wilt very effectively for decades, and this gene is widespread in oilseed hybrids. However, a new strain of V. dahliae has been identified, and recent greenhouse tests concluded that no commercial sunflower hybrids were found with resistance to strain NA-2.

The impact that Verticillium wilt may have on sunflower production in Nebraska is still unknown, as is whether we have the new strain of the pathogen. Nevertheless, knowing that the disease was found widely distributed across the growing area in 2008 suggests it could pose a risk, particularly if acreage with susceptible hybrids ever increases substantially to 2005 levels, approximately 100,000 acres.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension Publications Web site for more publications.

Index: Plant Disease

Sunflowers

Issued August 2009