G1502

Perennial Forages for Irrigated Pasture

Plant traits and selection guide for perennial forages for irrigated pasture in Nebraska, including information on recommended mixtures and species characteristics.

Jerry D. Volesky, Extension Range and Forage Specialist

Bruce E. Anderson, Extension Forage Specialist

James T. Nichols, retired Extension Range and Forage Specialist

- Important Plant Characteristics

- Cool- vs Warm-Season Grasses

- Cool- and Warm-Season Grass Mixtures

- Cool-Season Perennial Grasses

- Legumes for Irrigated Pasture

- Mixtures vs. Single-Species Stands

- Seed Known Varieties

- Limited Water Supply for Irrigation

Seeding the correct grasses and legumes is important for high production from irrigated pasture. The best management cannot overcome the limitations of poorly adapted species that lack the characteristics necessary for high production. Selecting the right plant materials is an important decision that should be made early in the planning stage.

This NebGuide describes the best perennial forage plants for permanent irrigated pasture. It does not include annuals such as sudangrass, forage sorghum, small grains, and turnips.

Important Plant Characteristics

Several plant characteristics are important and should be considered when planting irrigated pasture. Plants must be:

- adapted to and tolerant of the climatic, soil and site conditions;

- capable of producing high forage yields to achieve a high grazing capacity;

- readily consumed by the grazing animal and of good nutritive value;

- persistent and tolerant of grazing for a reasonably long pasture life;

- capable of good growth after grazing for sustained season-long production;

- readily established when using good cultural practices and easily obtained equipment; and

- compatible with other species when in a mixture.

No one species has the best of all of these characteristics, but many species are adequate in most or all characteristics and substantial improvement has been made through plant introductions and variety development. Additionally, mixtures can be formulated to combine characteristics from several plants into a pasture stand that will meet the producer’s needs.

Cool- vs Warm-Season Grasses

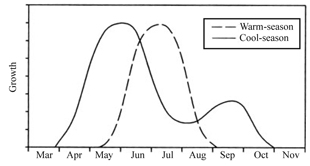

Cool-season grasses make their principal growth during the spring and have maximum rates of photosynthesis when air temperatures are between 65°F and 75°F. Warm-season grasses make their principal growth during the summer and reach maturity by late summer (Figure 1). Air temperatures for maximum rates of photosynthesis for warm-season species are between 85° and 100°F.

|

Most irrigated pastures are seeded almost exclusively to perennial cool-season species for the following reasons:

- Warm-season grasses usually have less total annual production because they do not actively grow during as much of the growing season as do cool-season grasses and legumes. In Nebraska, irrigated cool-season species can be stimulated to grow during the heat of summer at a reduced rate, but warm-season grasses cannot be made to grow at all during early spring and fall when soil and air temperatures are cool.

- As a group, cool-season grasses and legumes are well adapted to the environment of an irrigated pasture and respond readily to water and fertilizer.

- Cool-season species provide grazing when it is most critically needed by many livestock producers, especially when used in a complementary grazing system with warm-season native range.

Cool- and Warm-Season Grass Mixtures

Mixing cool- and warm-season grasses in the same irrigated pasture to obtain sustained season-long production is not advisable. Mixed stands are difficult to establish and, more importantly, they are difficult to manage to maintain desirable production from each grass type. If both types of grasses are desired, plant them as separate stands and manage them according to their respective needs. Information on warm-season grasses can be found in NebGuide G1908, Switchgrass, Big Bluestem, and Indiangrass For Grazing and Hay.

Cool-Season Perennial Grasses

Primary Grasses

The following section lists and describes important characteristics of the major cool-season perennial grasses that have the greatest known potential for use in irrigated pasture. These primary species, although not all the available varieties, have been evaluated in irrigated trials in Nebraska. Further information on specific varieties of these grasses can be found in EC120, Certified Perennial Grass Varieties Recommended for Nebraska.

Orchardgrass, a bunchgrass, has gained wide acceptance as an important irrigated pasture grass. It starts growth a little later in the spring than most other grasses described here; however, its ability to sustain production during the summer and late fall makes it an important part of irrigated pasture mixtures. It recovers rapidly after grazing if not grazed too short. Extreme cold and lack of snow cover can contribute to winter-kill on orchardgrass, especially if improper irrigation, fertilization, and grazing management have preceded a severe winter. Orchardgrass varieties vary in their winter hardiness and maturity grouping.

Smooth bromegrass is a very palatable sod-forming grass used widely for irrigated pasture and under dryland conditions in central and eastern Nebraska. It is included in mixtures because of its early growth and because it has rhizomes that help fill voids which may develop in a stand. It does not produce as well as some grasses during the hot summer and should not be seeded alone for irrigated pasture. Winter hardiness and persistence are rated high for smooth brome.

Meadow bromegrass has a bunch-type growth form. It reproduces vegetatively by vigorous tillering. Seedling vigor, winter hardiness, and stand establishment are excellent. It also makes excellent early growth and has good recovery after grazing. Fall growth can exceed that of smooth bromegrass. Because of its lax growth form, meadow brome is more suited for use in a mixture than when seeded alone.

Creeping foxtail is a sod-forming grass that is well adapted to wet site conditions. It should be included in mixtures for irrigated pastures that have wet or poorly drained areas that may have standing water during part of the growing season. It tolerates both moderately acidic (pH 5.6-6.0) and moderately alkaline (pH 7.9-8.4) soils and has survived a pH of 9.0 on wet soils. Creeping foxtail also is adapted to normal site conditions.

Although seedling vigor is poor and seedlings are slower to establish than other recommended grasses, tests have shown that creeping foxtail can be established successfully with other grasses in a mixture. It spreads rapidly by rhizomes, which helps it compete during establishment and also fills in any voids in the stand. Creeping foxtail makes much of its growth early in the spring and is one of the earliest maturing species available.

Intermediate wheatgrass and pubescent wheatgrass are closely related and similar sod-forming grasses. They can be very productive and provide excellent quality forage under irrigated pasture conditions when seeded in pure stands. They usually do not persist when seeded in a mixture with other highly competitive grasses. Thus, recommendations are to seed as a pure stand or as a mixture of the two wheatgrass types. Both types are drought tolerant and could be used in situations where there is a limited or irregular irrigation water supply.

Intermediate and pubescent wheatgrass have good seedling vigor and provide spring and late fall grazing. They do not produce as well during the hot summer as orchardgrass, tall fescue, or meadow brome and recovery after grazing is slow. Seedhead development is about two weeks later than other grasses commonly used for irrigated pasture, so they can be used later in the spring grazing cycle and still not be headed. They tolerate moderately high soil pH (8.0-8.5) and may be better adapted to sites that are poorly suited for other grasses.

Tall fescue is a deep-rooted bunchgrass, though it has short underground rhizomes that may eventually produce an even, durable sod. It can tolerate wet soils and soil pH that ranges from acidic to moderately alkaline. Tall fescue is less palatable than most other cool-season grasses and its palatability declines substantially if it is allowed to mature. Tall fescue has excellent fall growth that remains green after frost, providing good quality grazing in late fall. Summer growth usually is greater than for other cool-season grasses. Some tall fescue varieties contain an endophyte (fungus) that may cause livestock health problems if tall fescue constitutes the majority of the diet for an extended time. Low endophyte varieties may not cause these health problems, but generally are less persistent than the endophyte-infected varieties.

Festulolium is a cross between Italian ryegrass or perennial ryegrass and meadow fescue (or occasionally, tall fescue). It establishes rapidly and has better summer growth than many other cool-season grasses. Winter hardiness is usually better than with perennial ryegrass, but probably not as good as that of more commonly used grasses. Festulolium has shown good stand persistence in Nebraska.

Other Grasses

The following list describes characteristics of several other cool-season perennial grasses currently marketed. They may have potential for use in irrigated pastures or on specific sites; however, certain characteristics may make them less desirable for use in Nebraska than those listed above.

Perennial ryegrass is a short-lived bunchgrass with a shallow, fibrous root system. It has good seedling vigor and rapid stand establishment. Compared to other grasses, perennial ryegrass is shorter in stature but has a high leaf to stem ratio and yields high quality forage. Perennial ryegrass is best adapted to soils that have relatively high levels of fertility and organic matter. Cooler temperatures and consistently moist soil are needed for maximum production. Under these conditions, growth is rapid. Winter hardiness may be lacking in many varieties. In Nebraska, stands of perennial ryegrass tend to decline after two to three years.

Timothy is a winter-hardy bunchgrass that is well suited for hay production, although recent breeding efforts are concentrating on developing varieties more tolerant of grazing. Timothy has relatively shallow, fibrous roots adapted to water-logged soils, but it will grow in most soils if consistent moisture is adequate. Although very winter hardy, it is relatively short-lived in pasture mixes because its shade intolerance, slow recovery when grazed short, and poor reproduction make it less competitive.

Reed canarygrass is a tall, coarse sod-forming grass adapted to wet soils. It will tolerate standing water for extended periods or persist on other sites with adequate moisture, similar to creeping foxtail. Under irrigated pasture conditions, reed canarygrass shows a relatively good seasonal distribution of forage growth and grows well after grazing. It can be difficult to manage when grown in mixtures with other grasses. This species does contain potentially harmful alkaloids; however, low-alkaloid varieties are available.

Green wheatgrass, specifically the variety NewHy, is a hybrid developed from a cross between bluebunch wheatgrass and quackgrass. It is a long-lived perennial grass with a moderate amount of vegetative spread. Green wheatgrass has been used only sparingly, but may be useful on some sites because it is more saline tolerant than intermediate wheatgrass and nearly as tolerant as tall wheatgrass.

Tall wheatgrass is a tall, coarse, late-maturing bunchgrass. It is especially tolerant of saline-alkali soils with high water tables. The plant becomes coarse and unpalatable to livestock as it matures. These characteristics have generally limited the use of tall wheatgrass to revegetation of sites having saline-alkali soils.

Suggested seeding rates and mixtures are given in Table I. Seed size can vary substantially among species and varieties, resulting in different amounts sown per acre or per square foot.

| Table I. Examples of historically successful mixtures and species for seeding irrigated pastures in Nebraska. | ||||

| Species | Seeding rate

Lb. PLS/acre1 |

Mixture

composition (%) |

Seeds

per sq. ft. |

|

I |

Orchardgrass

Smooth bromegrass Meadow bromegrass Creeping foxtail Alfalfa Total |

5 3 5 1 2 16 |

62 8 8 14 8 100 |

75 9 9 17 10 120 |

II |

Orchardgrass Smooth bromegrass Meadow bromegrass Creeping foxtail Total |

5 4 7 1 17 |

64 |

75 12 13 17 117 |

III |

Orchardgrass Festulolium Tall fescue Meadow bromegrass Smooth bromegrass Creeping foxtail Alfalfa Total |

3 3 3 3.5 3 1 1.5 18 |

38 |

45 15 16 8 9 17 8 118 |

IV |

Orchardgrass Smooth bromegrass Alfalfa Total |

5 8 2 15 |

68 23 9 100 |

75 25 10 110 |

V |

Orchardgrass Smooth bromegrass Total |

6 10 16 |

74 26 100 |

90 31 121 |

VI |

Intermediate wheatgrass | 22 |

100 |

45 |

VII |

Alfalfa | 15 |

100 |

75 |

| 1PLS = Pure live seed: PLS = Germination x purity. | ||||

Legumes for Irrigated Pasture

Combining legumes with grasses in fields to be grazed can reduce nitrogen fertilizer needs, and in some situations, improve forage yield and quality. However, besides the potential for some species to cause bloat, legumes also can create additional challenges with respect to fertilization, weed control, irrigation, and grazing management. Consider these factors before assuming that legumes are the best and most economical way to produce irrigated forage for grazing.

Bloat is a major concern with some legume species. Other legumes do not cause bloat but have other limitations, such as difficulty in establishment, poor persistence, or low yield. Several management strategies can be used to reduce the potential for bloat. These generally can be classified into the categories of pasture establishment (type and amount in seed mixture), livestock diet supplements, and grazing management.

Several legumes have been evaluated for use in irrigated pasture. Alfalfa is the only legume to provide consistently reliable benefits to irrigated pastures in Nebraska. All other legumes either have specific limitations or lack sufficient research to permit recommending them at this time.

Primary Legume

Alfalfa usually is seeded in a mixture with grasses for irrigated pasture, but it also may be used alone (Table I). Many alfalfa varieties are available, and they vary greatly in yield potential, winter hardiness, disease and insect resistance, and grazing tolerance. When selecting an alfalfa variety, consider if it will be primarily grazed or harvested with a combination of haying and grazing. If grazing is the primary use, select one of the grazing-type varieties. Even though an alfalfa variety may be grazing tolerant, it still can cause bloat. Alfalfa plant breeders and scientists are working to develop alfalfa varieties with reduced or no potential for bloat; however, currently no alfalfa varieties recommended for Nebraska have reduced bloat potential.

The amount of alfalfa seed included in a mixture with other grasses typically ranges from one to four pounds per acre. Rates over two pounds per acre may result in a stand that has alfalfa producing a significant proportion of the available forage, increasing the potential for bloat. Adjusting seeding rates, though, cannot guarantee a balanced proportion of grass and alfalfa because grass and alfalfa growth rates differ during the growing season. In midsummer for example, grass growth may be slower than alfalfa, resulting in a higher proportion of alfalfa in the available forage.

Other Legumes

Cicer milkvetch is a nonbloating, long-lived legume with a vigorous, deep root system. Stems grow upright when young but tend to bend over as they grow. Pasture trials in west-central Nebraska have shown that animal gains from steers grazing only cicer milkvetch are considerably lower than those grazing either irrigated alfalfa or cool-season grasses. It is also slower and more difficult to establish than alfalfa or cool-season grasses. Lutana, Monarch, and Windsor are common varieties. Cicer milkvetch might be best suited to sites with moderate alkalinity.

Birdsfoot trefoil is a legume that does not cause bloating; however, its usefulness for irrigated pasture may be limited in Nebraska. Birdsfoot trefoil has been used successfully in the Corn Belt for nonirrigated pasture, but under irrigation it has a slower rate of recovery after grazing than some other legumes. Birdsfoot trefoil has moderate tolerance to salinity and alkalinity and high tolerance to acidity. It usually is best to include it only as part of a mixture with other legumes.

Red clover can be used as a part of the legume component in irrigated pasture because it establishes rapidly, giving high production for two to three years. Because it is short-lived, it must be reseeded every one or two years or periodically managed to allow it to reseed itself. Red clover has less of a tendency to cause bloat than alfalfa.

White clover has been used sparingly in irrigated pasture in Nebraska but its use is increasing due to the availability of more productive varieties. Ladino (large white clover) and Dutch (common white clover) are the two main types available. Varieties of Ladino white clover are typically much taller and more productive than Dutch white clover varieties. White clover persists well in pastures that are consistently grazed short, but will not compete well when higher yielding plants are allowed to grow tall. Similar to alfalfa, white clover may cause bloat.

Kura clover is a long-lived species that has an area of adaptation similar to white clover. It has poor seedling vigor and grows slowly during the establishment year. Once established, kura clover stands often thicken and survive a variety of conditions due to their deep rhizomatous root system. Kura clover has relatively poor summer growth and may cause bloat similar to red clover. It has not been evaluated under irrigated pasture conditions in Nebraska.

Alsike clover is a short-lived perennial but naturally reseeds if not grazed too short. It is best suited for soils too wet to support alfalfa or red clover. On drier soils, other legume species will perform better.

Mixtures vs. Single-Species Stands

Since no plant has all the desirable traits and qualities, mixtures are formulated using species with complementary characteristics. Each species is expected to contribute something of value. A mixture’s diversity may offer several benefits:

- Adaptation to a variety of soils or site types within a field

- Less establishment risk

- Improved seasonal growth distribution

- Improved long-term stand persistence due to a likelihood that not all species would be affected by grazing injury, disease, insects, or winterkill

- Improved diet quality and/or intake

- Effective soil moisture and nutrient use through the soil profile because of species differences in root type and depth

- Nitrogen fixation and increased forage quality by legumes

The species in a mixture should be similar enough in animal preference to allow management of the pasture as a whole, but diverse enough to contribute a range of beneficial traits. In multiple grass mixtures, like those described in Table I, combining competitive rhizomatous, sod-forming grasses with bunchgrasses often enhances long-term stand density.

Single-species stands, such as intermediate wheatgrass, may be desirable if they meet a very specific need and simplify management since that species’ requirements can be more easily met than if it were grown with other species. However, single-species stands are more susceptible to depletion by disease or winterkill and do not capitalize on the possible benefits previously described.

Seed Known Varieties

Plant materials selected for irrigated pasture should consist of known varieties. Varieties are selected to express important traits of a particular species and can influence performance of an irrigated pasture. Choosing superior varieties is just as important as choosing the right species. Information on specific grass varieties and adaptability to regions within Nebraska is available in EC120, Certified Perennial Grass Varieties Recommended for Nebraska, or at your local Extension office.

Limited Water Supply for Irrigation

The amount of irrigation water needed for maximum cool-season pasture production averages about 12 inches in eastern Nebraska and 18 to 20 inches in western Nebraska. The number of areas in the state where availability of groundwater for irrigation is limited will increase, especially in the Panhandle and southwest.

With limited water, efficient irrigation management is critical. For cool-season species, apply most of the water in the spring and early summer with a smaller amount in the fall, if possible. During these periods, irrigation efficiency is higher and the water is most effective in stimulating a growth response. Depending on the amount available, little or no water could be applied during July and August. Be sure to have other pasture or feedstuffs available during this time since irrigated pasture growth could be diminished greatly. In contrast, apply water to warm-season grasses from late spring through mid-summer to best match their water needs. For all species, level of production will be directly related to the amount of water provided.

Another option may be warm-season species such as switchgrass, big bluestem, and indiangrass. Their season of growth limits their use where water is abundant, but these grasses use limited moisture more efficiently than cool-season species. Their growth and water demands occur primarily from June through mid-August, which should influence where they are grown. Switchgrass matures earlier than the other grasses and usually is used best as a single-species planting because it quickly becomes less palatable than the other warm-season grasses, resulting in spotty grazing. Mixtures of big bluestem and indiangrass can provide good quality summer pasture. In the Panhandle, switchgrass is generally the warm-season species of choice because of the availability of adapted varieties.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension Publications Web site for more publications.

Index: Range and Forage

Pasture Management

2003, Revised February 2010