G1753

Cercospora Leaf Spot of Sugar Beet

The symptoms, factors favoring infection, prediction and control measures for Cercospora leaf spot of sugar beet is described in this NebGuide.

Robert M. Harveson, Extension Plant Pathologist

- Introduction

- Signs and Symptoms

- Conditions Favoring Cercospora Leaf Spot

- Predicting Cercospora Leaf Spot

- Disease Management

- Acknowledgment

Introduction

Cercospora leaf spot (CLS) is the most serious and destructive foliar disease of sugar beet in the central High Plains of western Nebraska, northeastern Colorado, and southeastern Wyoming. This disease is caused by the airborne fungus Cercospora beticola. CLS has a long history and has played a shaping role in sugar beet cultivation throughout the central and eastern production areas of the United States. This disease became a major limiting factor in early Nebraska production areas years ago, and was a primary reason for the shift of sugar beet production from eastern portions of the state to the west in the 1920s. The disease was of minor importance in western Nebraska until the mid-1980s, when it began to cause significant yield and sugar reductions throughout the North Platte River Valley.

Losses due to this disease can approach 40 percent, and are represented by both root tonnage and sugar percentage in roots. Beets with low sugar levels do not store well, and losses in storage result from increased storage decay. Profitable yields are additionally reduced due to greater levels of impurities in roots and increased sugar loss to molasses during processing.

Signs and Symptoms

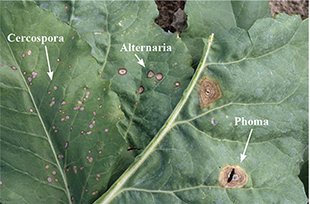

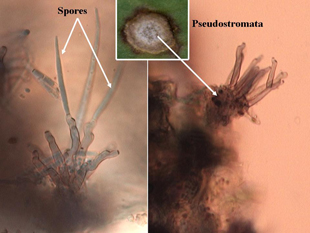

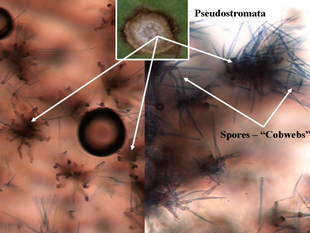

Individual leaf spots initially occur on older leaves and then progress to younger leaves. Individual lesions are approximately one-eighth inch in diameter with ash-colored centers and purple to brown borders, and are circular to oval shaped (Figure 1A). Cercospora leaf spot is distinguished from other leaf diseases (Alternaria, Phoma and bacterial leaf spots) by their smaller size and shape (Figure 2), and the presence of black spore-bearing structures, called pseudostromata, that form in the center of the lesions (Figure 3). These structures are easily seen as black dots with the aid of a hand lens (10X magnification) (Figure 4). During periods of high humidity the black dots will be covered with colorless fuzzy masses of spores resembling cobwebs (Figure 5), which serve as the source for secondary infections within fields that season.

As disease progresses, heavily infected leaves initially turn yellow (Figure 6). Individual spots may coalesce and form larger areas of dead tissue (Figure 1B), causing severely infected leaves to wither and die (Figure 7). Severely diseased plants can be viewed at a distance when dead or dying leaves appear above the canopy, giving a burned or scorched appearance (Figure 8). Disease often is unevenly distributed in fields, usually being more severe in protected areas adjacent to windbreaks formed by trees or taller crops, or other areas that may result in higher levels of humidity.

|

|

|

Figure 1A-B. Individual ash-colored circular lesions with dark brown borders (A). Advance infection with coalescing of individual lesions (B). |

Figure 2. Comparison of symptoms among other common foliar diseases of sugar beets. Reading from left to right: Cercospora, Alternaria, Phoma leaf spots. |

|

|

|

Figure 3. Microscopic side view of pseudostromata (spore-bearing structures) with spores attached (left) and empty (right). |

Figure 4. Macroscopic view of pseudostromata within lesion centers. |

|

|

|

Figure 5. Microscopic top view of pseudostromata without spores (left) and actively sporulating (right – “cobwebs”). |

Figure 6. Cercospora-infected leaves. Leaf at left is beginning to yellow and die. |

|

|

|

Figure 7. Severe infection with multiple leaves completely dried, dead and covered with masses of coalesced lesions. New growth emerging is unaffected. |

|

Conditions Favoring Cercospora Leaf Spot

The development of disease is highly dependent upon the presence of susceptible cultivars, adequate inoculum and environmental conditions characterized by periods of high humidity or leaf wetness periods longer than 11 hours and warm temperatures (> 60°F). Since leaf wetness is not routinely measured, relative humidity above 90 percent humidity can be used as a substitute. All of these factors must be present simultaneously for disease to begin and progress. For example, if a susceptible cultivar and adequate inoculum are present, but temperatures are too cold or warm or no moisture is on leaf surfaces, then infection cannot occur.

Generally, temperatures at night in western Nebraska are near the lower limits favoring disease development, but leaf wetness does occur (particularly with sprinkler irrigation). Very little infection will occur below 60°F or during periods of less than 11 hours of leaf wetness. Greater spore germination and leaf infection generally occurs when night temperatures exceed 60°F and day temperatures are between 80° and 90°F.

Initial inoculum potential depends on the survival of the fungus spores and spore-bearing structures (psuedostromata) from the previous year’s infected crop residue. Plants related to sugar beets such as weeds (lamb’s quarters and pigweed), and vegetable crops (chard, spinach, table beets) also may be a source of inoculum for infection in sugar beet. New spores produced under humid conditions on surviving pseudostromata can be carried by wind or splashing water to infect adjacent leaves and plants. Under favorable conditions in mid-summer, inoculum levels continue to increase and the life cycle of the disease may be completed within 10 days. Whenever leaf spots are observed, infection has taken place sometime in the previous 7-10 days, thus total infection present during favorable conditions is greater than what would be visible for up to seven days.

Predicting Cercospora Leaf Spot

Because of the strict environmental conditions needed for infection to occur, the disease is well suited to prediction of time periods when outbreaks would most likely be favorable. The prediction system is an estimate of the potential for disease development based on the relative humidity and temperature measured within fields. This system was developed in the late 1980s by UNL scientists, Albert Weiss and Eric Kerr, and still is being used today at the University of Nebraska Panhandle Research and Extension Center. Over the last 15 years the forecasting system has utilized up to 14 sites per season located in Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana. Results are then collated and disseminated to more than 40 sources, including consultants, researchers and media (Web, print, television, and radio).

This system assumes that a susceptible host and sufficient inoculum are present. Based on hours of leaf wetness or high relative humidity (> 90 percent) and temperature during this period, a daily infection value (DIV) is determined (Table I). If the two-day sum of the DIVs is seven or greater, there is a strong potential for infection and further disease development. If the sum is less than six, there is little likelihood of infection.

The following example will illustrate how to use the information in Table I. Assume that on Day 1 there were 13 hours of leaf wetness and the mean temperature during this period was 63°F. On Day 2, there were 15 hours of leaf wetness with a mean temperature of 65°F. The DIV for Day 1 was three while on Day 2 it was four. The sum of these two days was seven, resulting in conditions that would favor infection. If no symptoms were observed on leaves, then the DIV sum indicates that careful scouting is advised, and if symptoms were present, then a fungicide application would be warranted. If on Day 3, there were 12 hours of leaf wetness and the temperature during this period was 62°F, then the DIV sum for Days and 2 and 3 is 4+0=4, and no action would be necessary.

Table I. Daily infection values based on number of hours of high relative humidity (> 90 percent) or leaf wetness and concurrent average temperature during this period. |

||||||||||||

Hours |

Daily infection values |

|||||||||||

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 |

1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 |

2 2 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 |

4 3 3 2 2 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 |

5 4 4 4 3 3 2 2 2 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 |

5 5 5 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 |

6 6 6 5 5 5 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 0 |

6 6 6 5 5 5 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 0 |

6 6 6 5 5 5 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 0 |

6 6 6 5 5 5 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 0 |

6 6 6 5 5 5 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 0 |

6 6 6 6 5 5 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 0 |

6 6 6 6 5 5 5 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 0 |

| 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | |

Average temperature (°F) during periods of leaf wetness or high relative humidity |

||||||||||||

|

Disease Management

- Cultivation and rotation can reduce levels of overwintering inoculum and at least a three-year rotation is needed to reduce quantities of infested residue from a severely diseased crop. Tillage reduces inoculum levels by burying sugar beet residue, which encourages tissue decomposition, and reduces spore dispersal into a new crop. To minimize chances of spore dispersal into new crops, susceptible sugar beet cultivars should not be planted within 100 yards of last year’s severely infected crop.

- Using leaf spot-tolerant cultivars can significantly reduce disease severity and yield losses. Many new resistant cultivars are continually being developed that also are regionally adapted and contain multiple disease resistant packages. Resistant cultivars allow disease progress to develop more slowly, even under favorable conditions (Figure 9). Some of the most susceptible cultivars may have high yield potential in the absence of leaf spot, but fungicidal applications will be necessary for satisfactory yields when disease becomes severe.

- Fungicidal sprays may be necessary in fields where inoculum has carried over from the previous year, susceptible cultivars are grown, or environmental conditions are favorable for infection. The first symptoms of CLS in western Nebraska usually are observed in mid- to late July or early August. Since infections may already be established before symptoms appear, it is important to monitor environmental conditions daily for detecting favorable periods of infection after symptoms become apparent. Fungicides should then be applied after favorable conditions occur to prohibit rapid disease progress in these situations.

- Many different fungicides are registered for management of CLS. The most commonly used products for CLS management are listed in Table II. The majority of these fungicides are systemic in plants, and thus provide longer periods of protection than the protectant fungicides. Triphenyltin hydroxide is the protectant fungicide that is used to the greatest extent. Mancozeb and other dithiocarbamates are also examples of protectant fungicides, but rarely are used today in sugar beet production for CLS management.

Table II. Common fungicides registered for Cercospora leaf spot management in sugar beets |

|||

| Product | Fungicide |

Fungicide Class |

Pre-harvest interval (days) |

| Dithane SuperTin 80WP Headline Topsin M Eminent Proline |

Mancozeb Triphenyltin hydroxide Pyraclostrobin Thiophanate methyl Tetraconazole Prothioconazole |

Ethylenebisdithiocarbamate (EBDC) Organometalic Strobilurin Benzamidazol Triazol-sterol inhibiting Triazole |

14 21 7 21 14 7 |

- The greatest disadvantage of the systemic fungicides is that strains of the pathogen have developed resistance to them, particularly those in the benzamidazole class such as thiophanate methyl (Topsin® M). Other commonly used systemic fungicides include Eminent®, Headline®, and Proline®. The most important aspect to remember when using these products is to rotate fungicides with differing modes of action to avoid development of resistance in the pathogen. For example, a first application of Headline (strobilurin class) or Eminent (triazol class) should be followed by Super Tin®. If a third application is needed, use either Headline or Eminent or Proline, whichever one was not used in the first application.

- Best results for managing this disease in this region are achieved by integrating fungicide applications based on the Cercospora Alert system with the use of resistant cultivars and prudent cultural practices such as rotation and cultivation to reduce levels of infested residue.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to recognize the work and contributions of the previous UNL authors of this publication: Eric D. Kerr, former Extension Plant Pathologist; and Albert Weiss, Extension Agricultural Climatologist.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

DisclaimerReference to commercial products or trade names is made with the understanding that no discrimination is intended of those not mentioned and no endorsement by University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension is implied for those mentioned. |

Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension Publications website for more publications.

Index: Plant Diseases

Sugar Beet

2007, Revised October 2013