G2115

Managing Group Conflict

If a community group is going to be productive and successful, the entire group must be able to identify and resolve conflict successfully. Conflict management is a skill that can be learned.

Karla Trautman, Extension Specialist, South Dakota State University

Cheryl Burkhart-Kriesel, Extension Specialist, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Trudy Rice, Extension Educator, Kansas State University

- Four Strategies for Managing Conflict

- Factors in Choosing a Conflict Management Strategy

- Managing Interpersonal Conflict Worksheet

The human relationship is a complex and dynamic interaction. As living creatures, we need and crave the opportunity to interact with other humans by speaking, listening, and spending time with them. Most of this interaction tends to be mutual and cordial. Yet, at times, the interaction can be laced with tension and discord. If left alone, the tension can lead to conflict that may damage the relationship or even become volatile.

Conflict between individuals and within groups often occurs because people have differences of opinion, have different values and goals, or receive inaccurate information. Conflict is not always a bad thing. In many cases, conflict can lead to a better understanding of and response to issues. Conflict also can lead to creative problem solving and the initiation of innovative ideas. However, if conflict is suppressed and not addressed, it can lead to distrust and greater discord within the group.

For a community group to be productive and successful, group members and leaders need to be able to identify, address, and resolve conflict successfully. Like any other leadership skill, conflict management can be learned. The overall goal for conflict management is to find common ground (mutual goals and interests that all parties share) within the issue and use that as the foundation for resolution.

Effective conflict management flows from three factors:

- Recognizing that conflict exists

- Setting criteria for effective management

- Choosing a strategy that matches the situation

Successful conflict management also assumes three essential components:

- Conflicts are a normal part of life. It is not the presence or absence of conflict that determines the health of a

community. What matters is how conflict, when it arises, is managed.

- Not all conflicts can be resolved, but most can be successfully managed. Conflicts exist because there are differences of

value and opinion. In some instances, people may never reach agreement. However, even these conflicts can be managed in ways that

allow people to work together on other issues on which they do agree.

- You are part of the equation. Conflict requires two or more people. Remember, you are the only person that you can control. You can influence others but not fix them or control them.

When a conflict does arise, it is critical for the group (or the group leader) to address the situation quickly. Do not let conflict fester — it won’t go away and it won’t fix itself. Conflict is extremely difficult to address once emotion and history are attached to it.

Sometimes, trying to identify the true source of conflict can be difficult. We know that a person(s) is not in agreement with another person(s), but why? Is it a matter of perception, opinion, or a difference in values?

Good conflict management asks the following three questions to accurately identify the source of conflict between individuals or groups of people:

- Are our respective goals for this project incompatible? If so, why?

- What are the key arguments each person has on this issue? Remember that labeling other people in negative ways and blaming

them can cloud the ability to identify the root causes of a conflict. Look for the issue — not at the people involved or their

personalities.

- What are the consequences of this conflict? Consider how the conflict affects you, the other people involved, the community.

Once the true source of conflict is identified, it must be managed. A well-managed conflict will allow the individuals and/or groups involved to maintain (and maybe increase) their social capital with each other. In most cases, signs that a conflict is being well-managed include the following and should be considered as high priorities in the resolution process:

- The people involved do not lose their sense of self-worth. This means that the process used to solve the conflict and the

resulting actions do not cause those involved to lose their self-respect or the respect they have for the other person.

- The conflict stays focused on the issue. Do not let conflicts become personal attacks. Conflicts should always remain

focused on behaviors or actions — not on who someone is, their personality, or the emotions being expressed. Likewise, keep the

conflict focused on current issues — not something that happened previously.

- The interests of the partners in the conflict are identified, acknowledged, and taken into account. The issue in a conflict is most often about an incompatibility of goals. However, people often have interests in a conflict that go beyond the issue. These matter greatly to those involved and it likely affects their behavior during the conflict. For example, the fear of losing self-esteem, worries about what others will say, concerns about violating a value or principle. Often these interests are the underlying reason for the situation — the “why” of the conflict — and they generate more energy and emotion than the issue itself.

The worksheet on the next page will help you identify the true source of conflict and assist in the identification of strategies for resolving that conflict.

Four Strategies for Managing Conflict

Few conflicts can be managed with only one strategy. Effective community leaders do not depend on a “one size fits all” approach. In fact, they seek a variety of options — depending upon the situation.

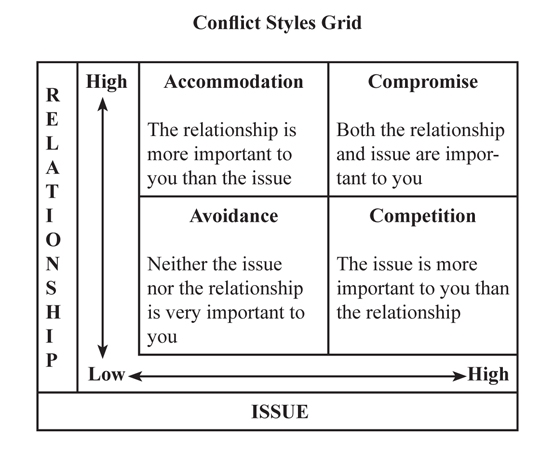

Every conflict involves two factors. First, conflicts are between people who are linked in some way — they are interdependent and have some type of relationship with each other. Secondly, conflicts occur when there are incompatible goals, meaning that in every conflict, there is an issue.

When managing a conflict, consider these two factors and ask how they play out in the situation.

Factors in Choosing a Conflict Management Strategy

RELATIONSHIP

| Low | High |

- What is our relationship? (friend, fellow committee member, spouse, co-worker)

- How important is this relationship to me?

ISSUE

| Low | High |

- What is the issue (the focus of the incompatible goals)?

- How important is the issue to me?

Now, chart your responses on the following grid. The grid will help identify some immediate strategies for the named conflict — though you may consider other strategies based on your comfort level and the evolution of the conflict.

Named Strategies:

Avoidance:

With this strategy, you simply stay away from the other person or groups involved in the conflict. The conflict remains un-named and no effort is made to resolve it.

This can be a useful short term strategy if:

- time is needed to calm down before discussing the issue, and

- a desire to avoid the situation exists because there is not a way to manage it.

Overuse of this conflict management tool can result in others seeing you or the group as uncaring and uninvolved.

Accommodation:

In this strategy, one of the conflict partners “gives in” on the issue so that the relationship can be maintained or enhanced. In this strategy, the conflict is named, and while one of the partners may disagree with the other’s position, the importance of the relationship outweighs the need to take a firm stand.

The risk of this strategy is that the individual (or group) who relinquishes his or her position may be seen as a “doormat” — someone who will not stand up for what he or she believes in.

Competition:

In this strategy, winning the position is more important than the relationship. Competition can be valid in value-driven conflicts that affect the community. However, remember to focus competition on the issue and not on the personality of the other person or group. The goal is not to make that person or group a loser, but rather to gain what is most important to you.

People or groups that overuse this strategy often compete on relatively minor issues and feel that they must win no matter what. As a result, they run the risk of “winning the battle but losing the war” within the community.

Compromise:

In this strategy, those involved in the conflict give up some components that matter to them, but they don’t give up everything. Both parties involved win some and lose some on the issue.

In this strategy, it can be difficult to determine the acceptable level of wins and losses and negotiate them. For this to work, both parties must see the wins and losses as fair, even if they are not equal. Be honest about what wins are needed and what losses will be tolerated.

Resource

Krile, James. (2006). The Community Leadership Handbook. Blandin Foundation. Published by Fieldstone Alliance (formerly Wilder Publishing Center).

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension Publications website for more publications.

Index: Communities & Leadership

Community Development

Issued February 2012